Understanding Role-Playing Games (RPGs)

Role-playing games or RPGs are games that allow us to create characters and stories that go beyond our real lives. We can make decisions that we may not have otherwise. For example, we can make risky choices, such as confronting a dragon or telling someone we care about them. When RPGs are played at a table, sometimes with minifigures, maps, and other props, we call these TTRPGs or Table-Top Role-Playing Games. We can also play RPGs virtually online or in video games.

In TTRPGs, there is typically one person who leads the group who is called the Game Master (GM). In Dungeons and Dragons, this can also be called the Dungeon Master (DM). Therapists who facilitate these groups often refer to themselves as Therapeutic Game Master or Therapeutic GM.

The Therapeutic Benefits of RPGs

RPGs are fun and engaging for people of all ages, but their benefits go far beyond the excitement of the game. RPGs have been used in both educational and therapeutic settings to teach children and adolescents new skills. They have also been used with adult populations in settings such as family therapy, hospitals and prisons to build community and enhance and practice skills.

The benefits of RPGs throughout these varied populations and age groups include the following:

Enhancing communication skills

Through their character, players get to practice their communication skills. The GM runs characters called NPCs (Non-Player Characters). The players can use the NPCs to gain more information that will help them with the game. For example, an NPC may know where the players need to go in order to complete their mission. Players need to be able to effectively practice back and forth conversations with the NPCs being played through a therapist to do this. Instead of having out of context conversations in a typical therapy session to practice this, the players are already immersed and engaged in the experience.

Fostering emotional intelligence

Players get to observe and experience the emotions of the other players and the NPCs. They get immediate feedback on choices that their character has made. For example, if a player decides they want to attack a nearby group of gnomes who other members may have wanted to talk to, reactions happen right away. Players might use their communication skills in order to do this. Other times, they express how upsetting a decision feels through their actions.

The therapist also gets to use the NPCs to express emotions and can make the emotions more explicit, if the group isn’t already doing so. An example of this is when a family with multiple autistic family members was playing a therapeutic game of Dungeons and Dragons, I heard one of the kids say how cool they thought their mom was in making certain decisions. The mom didn’t hear this comment, so I engaged the teenager in a conversation about it with an NPC. After the game, the family brought this up and had an entire conversation about all the things that their mom does that they love. Some very meaningful and needed conversations can happen during and after family gaming therapy sessions.

The therapist also gets to use the NPCs to express emotions and can make the emotions more explicit, if the group isn’t already doing so. An example of this is when a family with multiple autistic family members was playing a therapeutic game of Dungeons and Dragons, I heard one of the kids say how cool they thought their mom was in making certain decisions. The mom didn’t hear this comment, so I engaged the teenager in a conversation about it with an NPC. After the game, the family brought this up and had an entire conversation about all the things that their mom does that they love. Some very meaningful and needed conversations can happen during and after family gaming therapy sessions.

Improving problem-solving abilities

Built into the games are opportunities for players to solve problems. Players use their critical thinking skills to find solutions. These problems include how to get past a single obstacle or how to complete the mission, so it allows players to improve their problem solving abilities when taking both the present and future into consideration.

Building teamwork and collaboration

While working on all of the previously mentioned skills, players are also learning how to work together as a team. They must collaborate and make decisions together in order to advance the game. Not only do they need to work with each other, they also need to collaborate with the NPCs that the therapist is controlling. This allows the therapist to intentionally put the players into situations where they must work with others.

How RPGs are Integrated into Family Therapy

Designing therapeutic RPG sessions

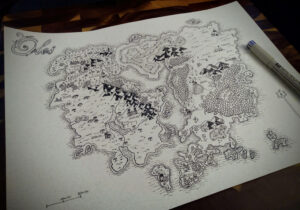

![]() RPGs are played in what can be referred to as “campaigns.” The GM puts a story together and has a specific mission in mind that the players will be working on throughout each session. There is usually an overall mission or goal to accomplish, along with smaller goals in each session. The smaller goals are oftentimes what enhances the therapeutic impacts of the game and can be adapted as needed to the particular family situation.

RPGs are played in what can be referred to as “campaigns.” The GM puts a story together and has a specific mission in mind that the players will be working on throughout each session. There is usually an overall mission or goal to accomplish, along with smaller goals in each session. The smaller goals are oftentimes what enhances the therapeutic impacts of the game and can be adapted as needed to the particular family situation.

These goals commonly reflect the therapist’s training and we use goals directly tied to the therapeutic interventions we have learned. For example, I use my training in Narrative Therapy to bring out the player’s stories and I use my training in Emotionally Focused Family Therapy to bring out the player’s emotions in real time.

It is becoming more common for therapists to run therapeutic groups that use RPGs. I run a group for teens that go through a campaign each quarter. Using RPGs for family therapy is quite new and innovative!

Customizing games for individual family needs

Each family and individual comes to therapy with their own unique history and dynamic. The beauty about RPGs is that they are infinitely customizable. The therapist will not only design the campaign to fit the needs of that family, they will also tailor the sessions to their needs. Since it can be impossible to predict exactly what choices each family member will make for their characters in any given scenario, the therapist works in real time with the goals in mind.

Steps for implementing RPGs in therapy settings

Running RPGs in therapy takes a great deal of intentional planning and forethought. The therapist must have a concise understanding of both the therapeutic tools that they want to use, along with the mechanics of the game, and ability to create a story. It is imperative that a family find a therapist that can meet all three of these components in order to give them the highest probability of success.

Once a family finds the right therapist for them to run a family therapy RPG campaign, they will likely meet with that therapist at least once before actually starting the game. Along with the intake paperwork, this first appointment allows the therapist to ascertain the family’s goals so that the game can be intentionally designed for them. It gives the family and the therapist a chance to see if it feels like a good fit. In the gaming community, this first meeting together is known as Session Zero.

The first session or Session Zero also allows the family members to say what they do and do not want as a part of the game. For example, if someone has a big fear of spiders, they may not want spiders to show up in the game. They can also talk about what kind of game they want it to be. For example, do they want it to be a fantasy world with dragons and swords? Or would they prefer the game to be based in a more real life setting? Do they want the components of weapons and fighting, or would they like this to look differently? A good therapeutic GM will be able to tailor the game to the family’s preferences, so that the tone, style, and other components meet their needs and comfortability level.

Case studies and success stories

The Anderson Family, which consisted of a mom, dad, teenage daughter, and teenage son, came to see me online during the height of the Covid pandemic. The daughter was experiencing some challenges related to a diagnosis of ADHD and cannabis use. The family was struggling with how to support her without becoming overly frustrated and placing all of the blame on her. They designed their game to be in a real life setting operating a ship. The dad chose to be a silly teenager in the game and the teens took on more of a parenting role, which allowed them to experience the frustrations that parents experience when kids don’t listen! They developed communication skills throughout their sessions together, particularly learning how to listen and respond appropriately to each other.

Another family I worked with had experienced the death of the husband/father. The mother brought in her three children for family gaming therapy. I used the Ghost Buster RPG to design a house that the family could explore in order to discover the secret that their husband/father had left behind. Each room had a different obstacle. For example, in one of the rooms, the family couldn’t use their voices to communicate. They had to practice other communication skills and cope with the fact that they couldn’t be heard. They ultimately made it through the obstacles and openly talked about the ways in which they were grieving. They came to understand the different ways that they each grieve and even talked about how to support each other in their grief.

Considerations

Addressing resistance and skepticism

There is some skepticism within the mental health community regarding this as a form of therapeutic treatment, especially among more classically trained psychologists and therapists. This is typically due to a lack of understanding and knowledge about the use of gaming in therapy. Oftentimes, they don’t realize that we don’t have to use the aspects of gaming that we don’t want in our game. For example, some families don’t want a fighting/battle aspect and there are still many options for that family.

Ensuring a safe environment for all participants

It is critical that all family members are given a safe environment to express themselves. If a family’s dynamics result in behaviors that are abusive, emotionally or otherwise, this must be addressed prior to starting a therapeutic gaming campaign. It should be understood what will and will not be tolerated, so that family members aren’t leaving a game feeling even more hurt.

It is also important that all participants have the ability to differentiate between reality and fantasy. While we certainly play out real dynamics within the game, it is a game. If there are family members who have diagnoses such as Schizophrenia, therapeutic gaming may not be the best fit for them.

Expanding accessibility and diversity

The gaming community has historically not been a safe place for people with differing identities. It is important that gaming therapists create and maintain safety and inclusivity for diverse populations within their games. This can be done creatively, such as having NPCs of different genders, abilities, and ethnicities, for example. A character who is blind may have other talents that they can utilize. I strive to make my games LGBTQ+ and neurodiversity affirming. I also strive to be aware and respectful of differing abilities, ethnicities, and experiences in general. RPGs give us the opportunity to build the kind of worlds that we want to live in. They give us tools to fight injustice and stand up for what is right. As a therapeutic GM, I believe I have the responsibility to uphold this.

What questions do you have about therapeutic gaming/family gaming therapy?

Blog written by Sentier therapist, Mary Devorak, MS LMFT (they/she)

Sources